Dear Readers: Thank you to everyone whose taken the time to read the newsletters over these last few weeks. While I certainly hope they’ve sparked ideas and conversations, I would also love to keep the discussion going. Please do forward this latest letter to anyone in your own networks who might be interested. And, as always, don’t hesitate to get in touch. Sending all my best to you and yours, A.

Just before nine o’clock on January 8, 1813, a larger than usual crowd gathered in the castle in York, England, as three shackled men were marched to the executioner’s platform. Over the course of ten minutes or so, the accused were given a chance to pray. One spoke emphatically and fervently, at first confessing his sins, but without admitting to his crime. Months earlier, the presiding judge had claimed: "You have been guilty of one of the greatest outrages that ever was committed in a civilized country... It is of infinite importance... that no mercy should be shown to any of you... and the sentence of the law... should be very speedily executed." As the executioner lowered the drop, the men were hung, their bodies exposed and still bound in irons. Some in the audience would remember how their forms seemed to shudder.

Between 1812 and 1813, countless numbers of Englishmen would be put to death. Often ranging from their late 20s to late 30s, they hadn’t conspired against the king or pillaged villages. They had, however, been unsettled and disadvantaged by rapid changes to the textile and cotton industries. And for the ones who sought recourse through the destruction of the new technologies: many were condemned to death. While we may not remember their faces, some still remember their names: the Luddites.

Today, we often use the term pejoratively, as a slur against the anti-adopters of technology: The older generation, perhaps, unwilling to enter an increasingly digital domain; the owners of a “dumb phone”; or the hapless fools merely incapable of changing with the times. Yet, the Luddites story is more than one of stubbornness to change; theirs is an overlooked smoke signal in our economic history.

The movement began among textile workers in England — first in Nottinghamshire, before spreading to places like Derbyshire, Cheshire, Lancashire, and Yorkshire. In short, wherever textile workers had previously prospered, their communities were now beset by a growing number of “obnoxious” machines replacing human hands only to generate poor-quality lace and cloth. Worse still, that cheaper fabric meant lower wages and dwindling jobs. The machines could make more, even if what they produced was worse. And the market? Well, quantity and efficiency were welcome.

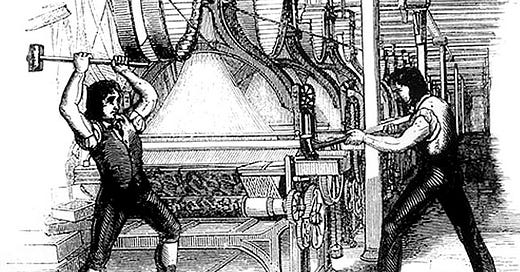

The Luddite cause started with calls for justice, often in the form of letters of warning to factory owners and local officials, urging them to remove the machines and restore their industry to trusted hands. Their letters (and eventual threats) were eponymously signed off with the name “Ned Ludd” or “King Ludd.” When these notes were ignored, the leaders organizing riots against factory owners or late-night raids to destroy the machines. Luddites would destroy water mills, power-looms, and weaving frames, the latest technologies to illustrate the pride and promise of English industrialization.

In this sense, the story of the Luddites is less a story about people against machines, but a story of defenders of workers’ rights, warning of the dangerous slipping balance between progress and peril. The speed of industrialization had taken the English countryside by storm, and the world — at large — had changed in ways perhaps previously unimaginable.

During King George III’s reign alone (1760-1820), England emerged from the Seven Years War as the pre-eminent naval power, and radically expanded the size of the British Empire [“on which the sun never sets,” a phrase first used by British statesmen Sir George Macartney, in 1773]. Within a decade of the war’s end, the Industrial Revolution was well underway. As Great Britain expanded to become the world’s leading commercial nation and advancements in manufacturing increased the standard of living for the general population, these changes served as the handmaidens of disadvantage and destitution for some. On February 27, 1812, Lord Byron warned the House of Lords:

During the short time I recently passed in Nottingham, not twelve hours elapsed without some fresh act of violence; and on that day I left the county I was informed that forty [weaving] Frames had been broken the preceding evening, as usual, without resistance and without detection... But whilst these outrages must be admitted to exist to an alarming extent, it cannot be denied that they have arisen from circumstances of the most unparalleled distress: the perseverance of these miserable men in their proceedings, tends to prove that nothing but absolute want could have driven a large, and once honest and industrious, body of the people, into the commission of excesses so hazardous to themselves, their families, and the community."1

Months later, the British parliament would pass the Frame Breaking Act, which labeled machine-breaking a capital offense. Further still, the government deployed 12,000 troops into areas where Luddites were active — a kind of counter-insurgency against the economically aggrieved. In short, the government turned its power against its own people, and specifically against communities left behind in the churn towards a more prosperous tomorrow.

While few might remember the Luddites' story, their struggle to put humanity first — to raise awareness of the effects of technological change — remains resonant, and their modern offspring continue to ask questions about whether technology can be fit into our lives without overwriting them.

Back in 1995, a man named Kirkpatrick Sale, an avowed “Neo-Luddite,” was interviewed by Kevin Kelly, then-editor of the technology-focused Wired magazine. Sale explained that his fellow-believers were no longer laborers or textile workers, but professors and thinkers, humanists and anarchists, and concerned parents. Asked what the Luddites had achieved and why their tradition was worth remembering, Sale said:

Luddites raised what was called … ‘the machinery question’: Whether machinery was simply to be for greater production by the industrialists, regardless of its consequences, or whether the people who were affected by these machines had some say in the matter of how they were to be used.

In Sale’s mind, “the Luddites also established themselves as the symbol of those who resist the new technologies and demand a voice in how they are to be used.” We might reasonably argue that support for this kind of critical thinking is on the rise and overdue. Recent (and popular) work, such as documentaries like The Social Dilemma, countless books,2 and articles, have endlessly explored this collision between technological change and our lived experience.

Further still, the Luddites' story should also serve as a particular kind of warning: government (and politics-as-practice) tends to play guarantor of prominent and even disruptive economic development. In 1812, the British government made the destruction of a new technology punishable by death. Not damage against the state or the monarch, but the damage done to private industry.

These trends are no less present in America, for instance, in the story of industrial boom and bust. And as information (and its management) replaces the hard goods — those textiles — of old, the balance of power between technology and society remains precarious.

As Tim Wu writes in his excellent book, The Master Switch: “Among the great questions in our time is whether our approach to the power of information should be informed by … that power’s political consequences [and] subject to our ingrained habit of balancing and checking any great power” or whether we should adopt the “alternative … and treat information markets just like any other, in which we tolerate, and even reward aggrandizement.” In other words, how should we protect our common public futures in light of private progress?

In our modern age, particularly in our information societies, the Big Tech giants have been similarly supported by (or at least not punished by) the state, in ways at least synonymous with the factory owners in England two centuries ago. And this should give us pause.

We’re often told that we will relive the past if we don’t learn from it. But that never happens. We don’t step in the same river twice. But our scrutiny of the historical record does indeed have a purpose. Smoke signals should be heeded. After all, history doesn’t need to repeat itself, but we might start to worry when it starts to rhyme.

What I’m reading:

Silicon Valley’s Safe Space by Cade Metz

After last week’s attempt to tackle the role of rationalism/positivism as a feature of the technologist creed, I stumbled on Metz’s New York Times article on Slate Star Codex, a polymathic blog frequented by many of the Silicon Valley brain trust. My own response to the article was mixed: caught between appreciating the importance of spaces for free expression and the awkward realization — discussed last week — that rationalism in the extreme can lead to dangerous forms of endgame thinking/logic. Still, it is worth reading.

Inside the Making of Facebook’s Supreme Court by Kate Klonick

What happens when a digital technology giant realizes wields the power of a state? They build a judiciary. Kate Klonick, a law professor, has carefully studied Facebook’s development, particularly in the area of information and speech. Her article “The New Governors” for the Harvard Law Review is an incredibly insightful investigation into how Facebook may see itself in the legal-political sense. Her latest piece is an interesting (and important) look into how FB self-regulation — regarding Trump’s permanent ban, no less — might (not) work.

What I’m listening to:

Yuval Noah Harari, the bestselling author of Sapiens, joins the Center for Humane Technology's crew to discuss what “futures” our rapidly evolving technologies might bring — and what that means for being human. P.s. The Center for Humane Technology was responsible for the documentary The Social Dilemma, discussed above.

Interestingly, Lord Byron — better known as the Romantic poet — only spoke three times in front of the House of Lords. Each time taking “unpopular sides.” Defense of the Luddite cause was the first.

Just some worth mentioning: Who Owns The Future by Jared Lanier; The Hype Machine by Sinan Aral, The Attention Merchants by Tim Wu; World Without Mind, Franklin Foer; The Age of Surveillance Capitalism by Shoshana Zuboff; Antisocial by Andrew Marantz; To Save Everything, Click Here by Evgeny Morozov.